[This post is being published out of order; the story is from September 2014]

Disclaimer: This post does not contain any technical information or advice for constructing or repairing bridges that are safe and structurally sound. Do not use anything written below as a guide for bridge construction or repair.

On the second Thursday of September, we arrived at the Pont (bridge) Pende, 40km south of Grimari on the Kuango road in Ouaka Préfecture, Central African Republic, and found ourselves unable to make the crossing in our Land Cruisers. Turning back northward, we stopped in Lakandja to speak with the mayor and some of the villagers. With Yvon, one of our superstar drivers, I explored the central section of the conglomeration of seven villages, creatively named Kandjia 1 through Kandjia 7, on foot.

In addition to a number of dirty wells, we were taken one kilometre down a path to a natural spring from which many villagers draw their water. The natural spring water flowing out of a rock face looked and smelled clean enough, but without testing it there’s no way to know whether it’s really safe.

However, as I stood chatting with a local man named Samedi (Saturday) at the edge of the shallow pool of water beneath the spring, I watched a woman dip her yellow plastic jerry can into the murky puddle at her feet, swish the brackish liquid around for a few seconds in a misguided effort to clean the container, empty the contents back into the brown water, then set the jerry can on the stone pedestal and reposition it until the stream of spring water was falling through the opening. The other women and girls followed suit. Clean water is only as safe as the receptacle in which it is stored, so it came as no surprise to hear the mayor tell of many cases of diarrhoea in the village.

After two hours looking around Lakandja, Yvon and I reunited with the medical team and together we agreed to return the following week to run a mobile clinic there.

We left Grimari just after 06:00 on the third Thursday (Thirdsday?) in September, driving south along the road that leads to Kuango. The medical team was made up of Alex, our Swedish doctor; Jean-Claude, Éric, and Félix, our nurses; and Dimanche, a local sécouriste. They would hire extra help onsite in Lakandja for crowd control, registration, temperature taking, and so forth; our polyvalent driver, Yvon, would handle the malaria rapid diagnostic tests.

Eric and Dimanche setting up for the mobile clinic:

The sign in the photo below says “Lakandja Central Market”. Destroyed by armed groups, the market was mostly just piles of mud bricks where shops had stood.

On my bridge building team I had two daily workers: Backer and Max. Backer had overseen the team of daily workers rebuilding the Pont Boungou a week earlier. Max was a regular daily worker at our base, and had proven to be sharp, conscientious, and hardworking. I chose these two to jointly lead a team of twenty daily workers drawn from the five villages nearest to the bridge.

Once we finished setting up the mobile clinic tables, tarps, and crowd control fencing in Lakandja, I jumped back into one of the two Land Cruisers with Zach (driver and self-appointed logistics assistant), Backer, and Max, and we set off southwards for the problematic Pont Pende, ten kilometres down the road.

The bridge was actually much more than problematic – it was nearly nonexistent. Two of the four original steel I-beams protruded from the fast-flowing water at French-friesian angles. The other two beams, each flipped on its side, still straddled the gap. A handful of crooked little tree trunks, bound together and set parallel to the beams, allowed commuters to cross on foot while rolling overburdened bicycles and motorcycles beside them on the metal beam – riding across would be too risky.

The day before, I’d sent letters by motorcycle to the leaders of nearby villages, asking them to identify 20 strong, hardworking men to build the bridge. I did my best to write in a tone both polite and pressing, with a handful of bureaucratic buzzwords sprinkled into the mix. Then, I printed the letters on official-looking MSF letterhead, signed with important-looking long blue pen strokes, and endorsed each one with a red rubber stamp. The rubber stamp is vital; in so many countries once colonised by Europeans, the systematic use of cachets to assign authority to an otherwise mundane document has persisted. Pro-tip: your stamp and signature must overlap at least partly, otherwise your document will be considered by some to have not been officially endorsed. This actually happened to me on more than one occasion.

When we arrived at the bridge (or rather, lack thereof), there must have been over 80 people waiting for us! It took just shy of an hour for us to sort everything out. First, we had to discuss our intentions and proposed plan of action with the mayor of Goussiema and the chefs from a number of nearby villages and quartiers. With their approval, we then needed to confirm the selection of twenty daily workers from the nearby villages. The names had been chosen the day before in each village: 6 from Lakandja, 2 from Koussingou, 2 from Bimbo, 2 from Zouniyaka, and 8 from Goussiema.

It was at this point that we hit a slight obstacle: in the week that had passed between our first and second visits to the Pont Pende, a team of youth had made a very slight improvement to the existing bridge. They had sprinkled some spindly tree branches and a bunch of stones to increase the bridge deck surface area, which was a modest improvement for pedestrians, but served no purpose at all for anything heavier than a motorbike. They had not added any kind of structural supports, so the bridge remained unsafe for vehicles.

Max demonstrated, by standing in the middle of the bridge and jumping up and down – the whole thing flexed and wobbled and creaked under the strain of his 60kg body. A 1750kg Land Cruiser, with a driver and cargo, would not likely make it more than a metre onto the bridge before taking a steep nosedive directly into the water. A motorcycle could make it across, but only at great risk.

We thanked them for the effort and sentiment, but explained that it would not be possible to cross this bridge without rebuilding it properly. The boys understood, but they asked us to pay them for the work they had done. I explained that the bridge they built wasn’t correctly done, that we appreciated the gesture, but that we couldn’t pay for work that was supposed to be done for free, and which wasn’t even done properly. The boys accepted this, but they asked to be paid as part of the new team. I asked how many they were, and the leader brought me a written list of twenty-five names! I was taken aback: the work they’d done should have taken three to four hours for a tiny group of two or three people. The situation began to smell fishy, but looking around I could see nobody holding a rod at the water’s edge.

The mayor of Goussiema intervened and decreed that the first group had accepted to fix the bridge as a community service and should not now be asking for payment; they had not done a good enough job, and they were mostly quite young, so they could not be hired as daily workers in the new group. They reluctantly accepted, but only after we agreed for them to remove the work they had done. For some reason, they tried to remove the entire bridge, old metal beams included, which led to an acute increase in volume as people converged to stop them from moving the beams – we had no plans to incorporate these beams into our new bridge, but no locals would be able to cross during the works if the beams were removed!

As this situation was heating and cooling like the oscillating fever typical of malaria, a half dozen daytime drunks lounged in deckchairs at the north end of the bridge, asking for work, stumbling into each other and the bushes, and taking turns expressing their ill will toward the group of daily workers whose names figured on the official list. Eventually, the drunks variously dispersed or fell asleep.

The team divided into two groups of ten, hacked away a hundred metres of roadside jungle-shrubbery in half an hour, then returned for further instruction. A boy brought a narrow bamboo chute on Zach’s instructions, held it to the ground and chopped it into 20cm segments with a few sharp wrist snaps of his machete. My knees creaked and cracked like the bamboo chute seconds before, as I crouched down to begin the demonstration at ground level. The bamboo pieces represented logs. First, I formed a rectangle out of a handful of logs set parallel to one another, then I positioned a second handful above that one, but rotated ninety degrees to run perpendicular to the first layer. As the layers built up, a little platform took shape: this was the bamblooprint for the footings on either side of the water. With the footings solidly installed, the team would then need to drag five sizable tree trunks to the site and rest the two ends of each trunk on the two footings, bridging the gap. After that, the bridge deck could be made using smaller trees laid crosswise and nailed onto the large tree trunks.

With the team already digging out the areas for installing the footings, Zach and I said our goodbyes and wished them all luck. Max and Backer remained with the twenty daily workers to manage the job on our behalf. Three days later – Sunday – I sent a motorbike with a digital camera to take photos and bring Backer back to Grimari for an update. We gave him further instructions, extra supplies, and tools, then sent him back out to work. He also took the equivalent of twenty dollars to split between the two coffee planters from whose land we had cut the five large trees, and another twenty dollars to pay for two nice cowhides. The leather would be softened in the water at the worksite, cut into strips, and used for lashing everything together.

On Wednesday I sent two motorbikes to bring Max and Backer back to Grimari, hoping the work was finished. With no phone network, the only way to communicate was to send motorbikes! In the afternoon, they returned, exhausted from the gruelling week’s work. Photos from the digital camera indicated success. We chatted for a while before sending them home to sleep.

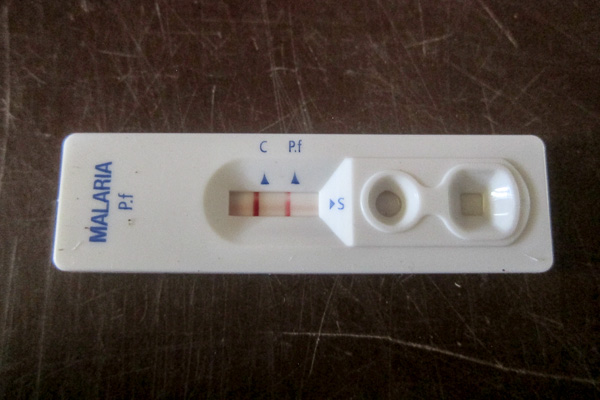

The next day, we were up at 05:00 for a 06:00 departure to Pouko, about 40km northwest of Grimari on the road leading toward Dekoa, for a mobile clinic. Yvon and I masterfully managed the 107 malaria rapid tests. By early afternoon, we had finished testing patients, so I asked Yvon to test me for fun. I’d been feeling unbelievably tired the day before, and had lower back pain that I attributed to my poor quality mattress and the rough roads we’d been travelling of late – both of these are common symptoms of malaria. A few minutes later, my test result came back positive, for the first time since April 2010.

The following morning, we were up again at 05:00 to hit the road at 06:00 with Zach, Yvon, and Alex. We picked up Max and Backer and headed to the Pont Pende to check the work. We hoped we could drive our Land Cruisers across!

We arrived to a waiting crowd – the daily workers were excited to be paid, but also eager to see if their efforts would satisfy our expectations. The bridge was indeed very well built; I was highly impressed, though I likely looked otherwise, owing to my malarial light-headedness and lethargy-betraying eyelids. Both Land Cruisers drove over the brand new Pont Pende, crossing from Grimari Sous-Préfecture southward into Kuango Sous-Préfecture, with neither anxiety nor accident.

I paid each daily worker for the week’s work with a colourful wad of cash rolled up, squashed flat, and sealed tightly into a six-by-eight centimetre pill bag, then we shook hands with the two mayors present for the bridge inauguration, pulled tight three point turns, and drove three hours back to Grimari.

I went to bed early that Saturday night, exhausted and feverish; by morning my pyjamas and bedding had trebled in mass, and my bodyweight had decreased by as much, from a night of plasmodial perspiration.

(Luckily, on Sunday I was able to relax by sleeping in until 07:00, spending the first half of the day on the road, and the other half manning the radio station and satcomms while two of our Land Cruisers and our DAF truck tried in vain to drive to Bambari before eventually leaving the truck with a village chief and returning in the Land Cruisers to Grimari. It was such a relaxing Sunday… once again, the only official non-working day of my week.)